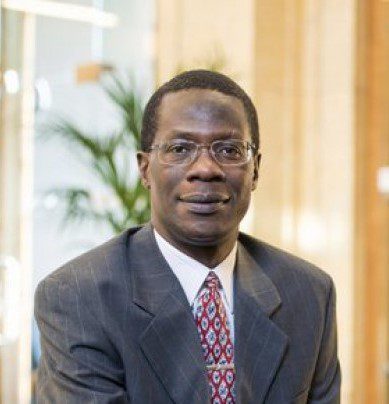

Robert Minge Mokaya OBE FRS is a Kenyan-British chemist who is Professor of Materials Chemistry and Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Global Engagement at the University of Nottingham. Mokaya holds a Royal Society Wolfson Merit Award.

Mokaya was born in Kenya. He attended the University of Nairobi, where he specialised in chemistry. After graduating he joined Unilever in Kenya. He moved to the University of Cambridge for his postgraduate studies, where he worked in the laboratory of William "Bill" Jones.

After graduating, Mokaya was awarded a junior research fellowship, and started his independent career at Trinity College, Cambridge.

In 1996 Mokaya was named an Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Advanced Fellow, and by 2000 he had been made a lecturer at the University of Nottingham. In 2008 he was appointed Professor of Materials Chemistry.

In 2017 Mokaya was awarded a Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award. Mokaya was appointed Pro Vice-Chancellor for Global Engagement at the University of Nottingham in 2019.

He was part of a Royal Society programme to strengthen the capacity of African researchers to design, synthesise and optimise porous materials.

He was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2022 New Year Honours for services to the chemical sciences.

In 2023, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS).

As of March 2022, Mokaya is the only Black chemistry professor in the UK and stated that UK Research and Innovation has rejected all of his funding applications.

Dr Marilyn Comrie OBE is an award winning serial entrepreneur, green tech innovator and board member of the Greater Manchester Local Enterprise Partnership. Her passion is developing the pipeline of diverse talent needed to fuel the green industrial revolution to tackle climate change. This includes Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic boys and girls, and young people from low-income backgrounds.

Honoured by HRH the Queen with an OBE for services to woman’s enterprise in 2009, and awarded the Kofi Annan African Leadership Excellence Award for contributions to attracting trade & investment into Africa, Marilyn is an inspirational role model, qualified leadership coach, chemistry graduate and strategic thinker.

She is a director of multi-award-winning e-motorsport STEM education pioneers, the Blair Project, principal founder of the Black United Representation Network which exists to tackle racial inequalities in Greater Manchester through wealth generation

Marilyn, is the CEO of new £4 million net zero industrialisation and electrification skills training centre within Manchester Science Park to strengthen supply chains and rapidly upskill, reskill and new skill home grown talent to drive green growth.

Opening in May 2024, the Manchester Innovation Activities Hub or MIAH will support the entire innovation chain from research, development and demonstration to commercialization and deployment, and deliver workforce skills training in automotive electrification, batteries, automation, robotics and hydrogen to plug gaps.

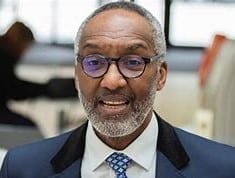

Dean Forbes is one of UK's most successful tech leaders. Dean has been named one of the UK’s 50 most ambitious business leaders by Lloyds Banking Group and The Daily Telegraph. He was also named in the J.P. Morgan sponsored Powerlist 2021, 2022 and 2023 as one of the 100 most influential Black people in the UK.

In a 20-year-career marked by many high points, he has successfully transformed several technology companies, building them into success stories for investors by delivering over $2bn in exit transactions.

The most recent of these was in March 2022, when under Dean’s leadership Forterro changed hands for €1bn, joining Europe’s growing numbers of ‘Tech Unicorns.’ Dean is one of very few CEOs in Europe to have achieved such value across multiple transactions.

Dean has been named one of the UK’s 50 most ambitious business leaders by Lloyds Banking Group and The Daily Telegraph. He was also named in the J.P. Morgan sponsored Powerlist 2021, 2022 and 2023 as one of the 100 most influential Black people in the UK.

At Forterro, Dean is currently leading huge potential for expansion. This is being achieved through a programme of both acquisitions and organic growth. The European-focused software company serves more than 11,000 small and midsized industrial companies and employs 1,600 people. Additionally, Dean is a partner at Corten Capital where he advises the firm on European technology acquisitions. He is also a member of their deal review committee. Part of Dean’s agreement with Corten Capital is that it will increase its support for founders and entrepreneurs from under-represented communities.

In terms of his early career, Dean secured his first job in the IT industry in his early 20s. By age 29, he had played a major role in the international growth of US software firm Primavera and was instrumental in its sale to Oracle for a reported $550m.

This led to a CEO role at KDS, a travel and expense management software company, which was acquired by American Express in the largest technology deal Amex had ever closed at the time.

Dean then became CEO at Core HR, a cloud-based HR and payroll solutions provider, driving its growth and then acquisition by the Access Group. There he took the role of president, leading the successful integration of Core HR into Access and establishing what is now the Access People division.

Dean is highly passionate about issues around social mobility and philanthropy and actively supports those with similar backgrounds to his own. Twice homeless and a primary carer in his teens for his disabled mother, Dean now campaigns and invests to level the playing field for the UK’s under-served communities through his not-for-profit foundation – The Forbes Family Group (FFG).

The foundation provides investment, networking and development support to young people and entrepreneurs from under-represented backgrounds. FFG has helped more than 1,170 young people move from difficult situations into education or into promising careers. FFG also donates meals, nappies and baby clothes to mothers in need and is an investor in a chain of not-for-profit pre-school and after-school clubs which provide free childcare for parents facing financial hardship. Dean is also a board trustee of the London-based African Caribbean Leukaemia Trust.

Malorie has written more than 70 books for children and young adults, including the Noughts and Crosses series, Thief and a science fiction thriller, Chasing the Stars.

Many of her books have also been adapted for stage and television, including a BAFTA Award-winning BBC production of Pig-Heart Boy (shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal), and the major BBC production of Noughts and Crosses which launched in 2020.

In 2005 Malorie was honoured with the Eleanor Farjeon Award in recognition of her distinguished contribution to the world of children’s books.

In 2008 she received an OBE for her services to children’s literature, and between 2013 and 2015 she was the Children’s Laureate.

Most recently Malorie was awarded the PEN Pinter Prize and was recognised as their International Writer of Courage.

Lastly, in 2022 she published her autobiography and memoir, Just Sayin’ - My Life in Words. See hereby an article by Patrice Lawrence reviewing her memoir.

In Just Sayin’ the former children’s laureate shares her sometimes enraging story of rejection, determination and resilience. Guardian article by Patrice Lawrence (Wed, 19 Oct 2022)

At the beginning of Malorie Blackman’s engrossing and often shocking memoir, the former children’s laureate asks: “Why am I an author?” What she goes on to tell us certainly shows how she was able to succeed: absolute determination, powered by rejection and by the love and support of others. The memoir eschews a strictly chronological approach. There are five themes – Wonder, Loss, Anger, Perseverance, Representation and Love. The prose and occasional poem contain intimate, often painful and sometimes funny insights into the author’s life.

Born in south London in 1962, Blackman’s parents were part of what’s now referred to as the Windrush generation – British citizens encouraged to move to the UK after the war. In Barbados, her father had been a master carpenter. In the UK he drove buses. Her mother worked in a factory, denied further education back home, since school money was saved for the boys. It was a “staggered” family – Blackman’s parents coming to England first, her older Barbados-born siblings joining them later.

Blackman was often lonely, but she was an avid learner. The public library was her sanctuary, comic books her solace. When she was 13, she arrived home from school to find a letter taped to her mother’s dressing table mirror: her father had left the family. The next day, the bailiffs came – Dad had gambled away the mortgage money. Blackman, her mother and younger siblings had an hour to leave for good, taking only what they could carry. Her beloved comic books had to stay behind.

Just Sayin’ is not a misery memoir, but there were many times I felt angry on its author’s behalf. The family was first housed in a stinking cockroach - and mouse -

infested flat – “urine on bass, damp on keyboards and stale sweat on drums”. The windows didn’t open. There was no fridge, a hotplate instead of a cooker and clothes were washed in the brown-stained bathtub and dried as well as they could be without central heating.

Food was “cornflakes for breakfast, when we had milk” and streaky bacon fried with flattened dumplings made from flour, sugar and water, every meal for months. Blackman passed her 11-plus but had no money for the bus fare to the grammar school. She still went, walking the six-mile return trip, sometimes silently crying with exhaustion. She told no one at school about her humiliating circumstances.

She knew nothing of the illness, discovering it could be life-limiting from consultants casually talking by her bed.

There are other moments that made me prickle with fury. Of course, I expected racism. Most people of colour swap similar tales. Her dream of teaching English literature was sunk by a teacher who was adamant that Black people did not do that. Then, there is the account of sexual assault by white teenage boys in a cinema, and her fury at the grown men of all backgrounds who felt no shame in sexually harassing her from the age of 11.

But for me, the most shocking moment came at the hands of health professionals. When she collapsed in her university bedroom, she was rushed to hospital and her healthy appendix was removed. She found out she had sickle cell anaemia, not appendicitis, from her friend, whom the doctors told before her. She knew nothing of the illness, discovering that it could be a life-limiting condition from consultants casually talking by her bed when they thought she was asleep – she heard that she would not live beyond the age of 30. Many years later, while she was pregnant, a doctor and nurse ignored the seriousness of her urine retention. A catheter was jammed in so violently it caused her unborn daughter’s death.

Yet, overwhelmingly, this is a book about survival and success. Blackman’s determination to be published will put many writers -– me among them – to shame. She signed up for evening classes to develop her writing skills, but only thought of writing for children after wandering around a central London bookshop, where she hoped to find the diverse books that were missing from her own childhood. “I looked and I searched and I practically lost my eyesight trying to find a Black child – any Black child – on a book cover.” She saw talented peers give up dreams of publication after a couple of rejections. She queued outside the sadly defunct Silver Moon Bookshop on Charing Cross Road so that Alice Walker could sign her copy of The Color Purple. She asked the bemused American author to write “Don’t give up” on the inside cover. After 82 rejection letters, Blackman’s first stories were published by The Women’s Press in an anthology for teenagers.

The challenges continued – pain and debilitation from poorly treated sickle cell anaemia, the constant rejections of manuscripts, and the deaths of two unborn babies. But tenacity and sheer hard work continued, too – and eventually allowed her to change the face of UK children’s publishing.

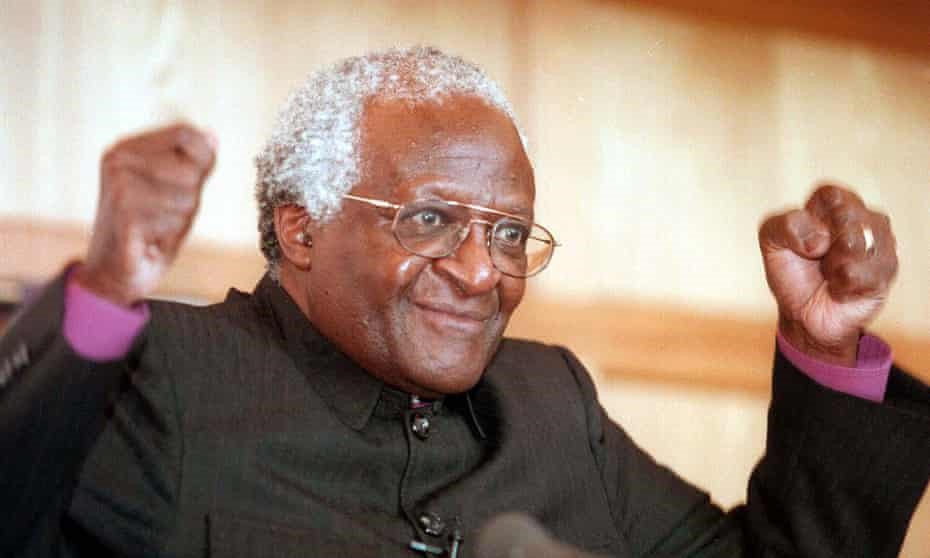

Anglican archbishop who fought against apartheid in South Africa and led the subsequent Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In 1931 Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born 7 October 1931 and died 26 December 2021. He was born in Klerksdorp, a predominantly Afrikaner farming town, 100 miles south-west of Johannesburg. His father, Zachariah, a Xhosa, was head teacher of the local Methodist primary school. His mother, Aletta, a Mosotho, was a domestic servant. The children were all given both European and African names and spoke Xhosa, Sotho and Tswana. Later, Tutu also learned Afrikaans and English. At the age of 14 he contracted tuberculosis and over the course of 20 months in hospital he developed a lifelong friendship with Father Trevor Huddleston, the Anglican missionary priest from Britain who, as one of the most prominent opponents of apartheid inside and outside South Africa, became his religious inspiration and mentor.

In 1948, when the apartheid regime was voted into office in South Africa, Desmond Tutu was 17. It was not until the late 1960s, as the future Anglican archbishop of Cape Town approached 40, that the concept of black liberation caused him to widen his horizons, and it was only in the mid-70s that he aligned himself with the liberation struggle.

Tutu, who has died aged 90, developed late in this respect because at first he was wholly a man of the church. He never wanted to enter politics. Church and state were locked in combat, however, and choices had to be made. Anglicans, Catholics, Methodists and others condemned apartheid, while the Dutch Reformed churches in South Africa defended it.

When Tutu became the first black Anglican dean of Johannesburg in 1975 he was, according to his biographer, Shirley du Boulay, “less politically aware than one might have expected. His contribution to the liberation of his people had been in becoming a good priest.”

Tutu obtained a teaching diploma in 1953 and a BA degree by correspondence a year later. He taught at high schools in Johannesburg (1954) and Krugersdorp (1955-57), before leaving to train at St Peter’s theological college, Rosettenville. Ordained a priest in 1961, he served in an African township.

His entry into the liberation struggle followed the years he spent abroad. From 1962 until 1966 he was in London, where he secured a master’s in theology at King’s College. He served as a curate in Golders Green and at Bletchingley, Surrey, where initially standoffish Tories took him to their hearts.

After teaching at the Federal Theological Seminary in the town of Alice in the Eastern Cape province, Tutu went back to Britain from 1972 until 1975 as associate director of the Theological Education Fund of the World Council of Churches. From 1976 to 1978 he served as bishop of Lesotho, returning to Johannesburg to take up the high-profile post of general secretary of the South African Council of Churches (SACC), from which the pro-apartheid Afrikaans churches had cut themselves loose.

That appointment effectively marked the end of Tutu’s political innocence. He had seen the uglier side of Africa, and although his travels separated him from the struggle in his own country, they also moulded him, giving him a wider outlook, more self-confidence and a growing revulsion against race discrimination. In spite of passport restrictions, in the early 80s Tutu was probably the most travelled churchman in the world after Pope John Paul II. Britain was always a sanctuary for him. The turning point on that score, said Tutu, came when everyone at King’s College London treated him like anyone else. “So my gratitude to England and my gratitude to King’s is that I have discovered who I am.”

In more than one sense Tutu became Nelson Mandela’s precursor. Both men foresaw the inevitability of liberation. Both were sufficiently above racial issues to know that, ultimately, what mattered (at least for the transition from apartheid to non-racial rule) would be reconciliation among South Africa’s races. Once the apartheid government accepted the inexorability of change, as it began to do in the 1980s, the role of the prophet changed. “Demands for justice are replaced by demands for reconciliation.”

However outraged they might have been by their experiences under apartheid, both Tutu and Mandela put their personal feelings aside. In African terms, both were relatively privileged, Mandela (of Xhosa royalty) even more than the highly educated Tutu. There were differences, of course. Tutu was excitable, passionate, easily hurt; Mandela composed and imperious. In the difficult dying days of apartheid the media, especially the state-controlled broadcasting corporation (SABC), demonised Tutu as the man most white South Africans loved to hate.

But Tutu blazed the trail. When Mandela said the same things 10 years later, his words sounded fitting; when Tutu uttered them he outraged even his Anglican brethren. In 1980, he forecast that South Africa would have a black leader within five to 10 years (it took 14). The reason why many white people were so venomous was not only that Tutu told them that tomorrow would not be theirs, but that he did it with such certainty.

The entertaining, excitable, impish little man was an old-style prophet, but also one with a dry sense of humour. White people, he observed, saw him as a politician trying hard to be a bishop, with “horns under my funny bishop’s hat and my tail tucked away under my trailing cape”. His wry assessment of the impact of their arrival in South Africa was: “We had the land and they had the Bible. Then they said, ‘Let us pray,’ and we closed our eyes. When we opened them again, they had the land and we had the Bible.”

At times, Tutu was the despair of his friends. Once he said that if the Russians came to South Africa, they would be welcomed as liberators. An associate sighed, “He had this habit of going over the top.” Tutu’s support of international sanctions against South Africa caused a huge eruption among white people and also in his own church. Some liberal white South Africans classified Tutu’s Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 as foreign interference.

Tutu could never execute the politician’s soft-shoe shuffle. He spoke his mind, was always his own man, never trendy or fully in the political mainstream. Initially, he had been drawn to the Black Consciousness Movement and to American ideas of “black theology”, but he shifted closer to the United Democratic Front (UDF), the exiled ANC’s internal surrogate.

Sparing the sensitivities of white Anglicans was scarcely Tutu’s concern. By the time he arrived at the SACC in March 1978, the organisation was becoming a microcosm of a future, non-racial South Africa. Tutu aired his own opinions, sometimes provocatively, on world affairs. He blasted the Soviet puppet regime in Afghanistan and, simultaneously, the US for supporting the Contras in Nicaragua and Israel for bombing Beirut.

One of his more spectacular outbursts was his condemnation as “nauseating” and “the pits” of a speech by Ronald Reagan in 1988, in which the US president defended the continued involvement of American companies in the South African economy. For his part, said Tutu, “America and the west can go to hell.” Later, in his engaging way, he half-apologised, saying that perhaps he should have used “less salty language”. Patrick Buchanan, Reagan’s chief media adviser, snapped back, “Whatever his moral splendour, the bishop is a political ignoramus.”

By then, Tutu was accustomed to storms breaking over his head. In 1979, on a visit to Denmark, he criticised that country’s purchase of South African coal, thereby signalling his support for sanctions. On his return to South Africa, he was summoned to a meeting with two cabinet ministers, who asked him to retract or face possible action, not only against himself, but against the SACC as well.

However, the organisation rallied, telling the government of P.W. Botha that a retraction could constitute a denial of Tutu’s prophetic calling. It added, though, that it was willing to meet the government to discuss fundamental reform. It was a turning point in the mighty church v state conflict that had rocked the country since the 50s. The Anglican Church was flexing its muscles. Tutu advised the government to stop playing God. During the Christian church’s 2,000-year existence, he said, tyrants had acted against it, arresting its followers, killing them, proscribing their faith. “If they take the SACC and the churches on, let them know they are taking on the Church of Jesus Christ.”

In 1980, Tutu and fellow clergymen went to Pretoria to meet Botha, six cabinet ministers and two deputy ministers. It was not an easy decision. Critics, clergy among them, warned Tutu’s delegation they were wasting their time, even betraying the struggle. It was Tutu’s intuitive genius to know when meeting an enemy showed strength rather than weakness. In 1982, the then archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, sent a five-member delegation to South Africa to demonstrate world support for the SACC – “to make the point [to the apartheid government] that you are not simply dealing with a domestic matter. If you touch Desmond Tutu, you touch a world family of Christians.”

Tutu did not meet Botha again until 1986 when, accompanied by the liberal Afrikaner churchman Beyers Naudé, he was received at the state president’s official residence in Cape Town. Tutu met Botha on two further occasions in 1986, around the time the white regime was starting to meet Mandela secretly in prison. The days of apartheid were numbered, even though few realised it.

Tutu thus began his ascent in the Anglican Church just as it far-sightedly started to adjust to a changing South Africa. Soon after receiving the Nobel peace prize, he left the SACC to become the first black bishop of Johannesburg (1985-86). The electoral assembly of the diocese consisted of 214 delegates – all the clergy plus one layman from each congregation. The conservative, mostly white, priests blocked Tutu, while the black priests blocked the election of a white bishop. Unable to deliver the required two-thirds majority, the assembly passed the decision to the synod of bishops, who chose the black candidate.

In April 1986, Tutu was elected to the highest Anglican post in South Africa as archbishop of Cape Town, and that September was enthroned in St George’s Cathedral. This was followed by his unanimous election as head of the All-Africa Conference of Churches at its gathering in Togo.

By then Tutu was in the thick of politics. Arrested for taking part in an illegal march, he was fined, imprisoned for a night and had his passport withdrawn. When it was returned, the irrepressible prelate promptly visited the pope, whereupon his passport was temporarily withdrawn again.

Defying the Botha government, Tutu met the ANC-in-exile at its Zambian headquarters, where – ever his own man – he informed it that, while he supported its aim of a non-racial, democratic South Africa, he could not associate himself with the armed struggle. The ANC at first refused to end it but later agreed to suspend it.

Tutu had first met Mandela in the 1950s, when the latter was an adjudicator in an inter-school debate in which Tutu was a participant. He did not see Mandela again until the latter’s release from prison in 1990, although they corresponded while Mandela was a prisoner on Robben Island. When Tutu received the Nobel Prize, the ANC organised a celebration for him, and on Mandela’s release from prison, he stayed at Tutu’s official archbishop’s residence in Cape Town.

“With calls coming from all over the world, and even the White House,” Tutu said, “it was quite impossible to spend time with him. Even then he was ever gracious with his old-world courtesy ... His regal dignity is quite humble.” There is just a hint here of the tension that later affected the relationship.

Tutu recalled that, at a state banquet for the president of Uganda, the former president FW de Klerk had not been placed at the top table. Mandela “was genuinely concerned that De Klerk had been treated so offhandedly”. However, said Tutu, Mandela could also be “horribly stubborn”. For his part, Mandela remarked, light-heartedly, on the trouble Tutu had caused him.

Tutu married Leah Nomalizo Shinxani in 1955. They had four children. A journalist noted many years later: “It’s fair to say that only an astute, humorous and strong woman could have survived life with Tutu,” while a close friend said, “I think she has a helluva hard time. Desmond gives himself so much to everybody that I’m not sure whether there is a lot left for Leah.”

As the ANC leaders returned from exile and prison, Tutu modestly withdrew to the wings, returning to his spiritual calling. But Mandela invited him to take the chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), with a mandate not to conduct Nuremberg-style trials, but to effect reconciliation by uncovering “gross violations of human rights” committed during the apartheid years – by all sides, including the ANC. It was an offer Tutu could not refuse.

Appointed in December 1995, the TRC delivered its final five-volume report to Mandela in November 1998. By then Tutu had been receiving treatment in the US for prostate cancer. His illness had a profound effect, making him consciously savour his remaining years and turn away from public life, towards his God and his wife.

The TRC – the climax of Tutu’s career – was both praised and disparaged. Historians will long debate what it achieved. It could have investigated an estimated 100,000 violations of human rights, protracting the hearings endlessly, but it focused on the worst cases, finding time to listen to mea culpas and semi-apologies from the business community, the media, churches and others.

For Tutu, the 1997 hearing at which De Klerk refused to accept political responsibility for the assassinations, kidnappings, torture and assorted crimes committed by agents of the apartheid state was traumatic. De Klerk made the extraordinary submission that apartheid was “a well-intentioned failure” – and that he and his predecessor, Botha, had presided over two final phases of “reform and transformation”. It was quite incorrect, De Klerk told the commission, “to refer to our administrations as the apartheid government. We were primarily concerned with the dismantling of apartheid.”

Tutu confessed that there were times when his Christian charity was strained to the limit. He described the white regime’s chemical and biological warfare programme under Botha as the “most diabolical aspect of apartheid”. Tutu, however, warmly commended De Klerk’s speech in February 1990 unbanning liberation movements, and when he was consulted by the Norwegian Nobel committee for advice on whether to award a joint peace prize to Mandela and De Klerk in 1993, he endorsed it.

But, he said later, “had I known then what I know now, I would have opposed it vehemently”. As for Botha, then in retirement and preparing to remarry, the TRC was a “circus” and he would not “perform” before it. Fined for contempt of court, he remained defiant to the end. The ANC’s response to the TRC report was almost as dismaying for Tutu. The report recorded that the ANC, in exile beyond South Africa’s borders for 30 years, had committed gross violations in its detention camps, torturing and executing suspected informers, rebellious members and others, and that, even after its unbanning in 1990, it had committed further crimes, including murder, mainly against black political opponents. Friends said he was saddened and perplexed by the ferocity of the criticism of the TRC by the ANC, the white right wing and some mainstream liberals.

Tutu saw the party’s attack on the TRC as a betrayal of the ANC’s finest moral traditions. But he was comforted by the knowledge that many ANC members and supporters, including Mandela (no longer president of the ANC though still president of the country when the TRC report was published), were similarly disturbed by their organisation’s official response.

This dissent within the ANC prevented a lasting rupture between Tutu, the country’s “most prominent moral lodestar”, and the ANC. The ANC applied for an injunction to prevent publication of the TRC’s report (Mandela dissented), but the court rejected it. It was an inexplicable blunder by the ANC leadership, and an appalled Tutu exclaimed, “I have struggled against a tyranny. I did not do this in order to substitute another.”

Having stepped down as archbishop in 1996 Tutu left for the US in October 1998 to take up a two- year theology professorship at Emory University in Atlanta. Overwhelmed by invitations to address other gatherings and institutions across the US, he turned most of them down, so that he could carry his workload at Emory, pace himself through his illness and spend more time with Leah. In Atlanta, he completed his major work, No Future Without Forgiveness, published in 1999, while remaining in close touch with those parts of the TRC that were still at work.

For all its shortcomings, Tutu’s TRC was an extraordinary episode in South Africa’s history. Even if it used controversial methods and failed to deliver universal reconciliation (many white people felt they were simply in the dock), at least it uncovered much of the truth. The “gross violations” were a festering sore that had to be cleansed. Some dozen other countries have conducted their own truth commissions, but South Africa’s was the most remarkable and, for this achievement, the archbishop can take his bow before history.

Tutu was credited with coining the term “rainbow nation” for the non-racial South Africa that he, Mandela and their various supporters wanted to rise from the ashes of apartheid. On his retirement as archbishop, Mandela said of Tutu at a service of thanksgiving: “His joy in our diversity and his spirit of forgiveness are as much part of his immeasurable contribution to our nation as his passion for justice and his solidarity with the poor.”

In his final years, remarkably active in the light of his cancer, Tutu campaigned in many parts of the world for human rights and freedoms, and was often seen in his beloved London. He announced that he would retire from public life on his 79th birthday, in October 2010. But the flow of comments on a wide range of social and political issues continued unabated.

In 2013 he announced he could no longer vote for the ruling ANC because of its corruption, inequality and use of violence, and its failure to tackle violent xenophobia and poverty in the townships. At the time of his 85th birthday, in 2016, he called for the right to assisted dying, and in 2020 he joined other faith leaders in calling for an end to the criminalisation of LGBTQ+ people.

He continued in his advanced years to receive honours and awards from many countries, and in 2015 he was made a Companion of Honour (CH) by Britain.

Tech industry pioneer Jacky Wright is named the UK’s most influential black Briton by The Powerlist 2022 which is the annual list of the UK’s most powerful people of African, African Caribbean and African American heritage.

Wright, Chief Digital Officer and Corporate Vice President at Microsoft US, is widely regarded across the world as one of the most influential black women in the tech industry. Wright was born in north London, but works in the United States; she has been vocal about the need for the tech industry to address its lack of diversity and has been the driving force behind a number of innovative programmes to achieve this goal.

Before working at Microsoft Wright held high profile roles at BP, General Electric and Andersen Consulting. In 2017 she was chosen to be Chief Digital Information Officer at HM Revenue and Customs. She spent two years in the position on secondment, then she returned to Microsoft in 2019.

Speaking about how she felt to top the latest Powerlist she told The Voice newspaper: “It feels surreal. I’m one of those people who likes to do what they do quietly. I’m all about change; I’ve been doing it my entire career, and I’ve focused on how we make this world a better place.”

She hopes that the award would further encourage a debate, which began last year in the midst of the Black Lives Matter protests, about making the tech industry more diverse.

“I think we’re starting to see companies take bold action” she said. “The question is, will it be enduring? Or will it fall off? I think we are at this point where we have to maintain vigilance in terms of holding companies accountable. Because if we don’t the next big thing will come up, and we would have forgotten what we were pledging to do.”

While acknowledging that she is seen as a role model for many people from diverse backgrounds wanting to get into the tech industry, Wright also pays tribute to her family who she says played a key role in her success.

“I grew up in a family where education was non-negotiable. You knew you were going to university, there were no if or buts about it,” she recalls.

“But I also came from a family that always spoke about their culture and where they came from. My dad and my mum came from Jamaica. Also my dad always spoke about Africa, whether it be South Africa, whether it be the Congo, or East Africa. Learning this history, played a key role in my psyche, in terms of knowing who I am, where I come from and having the confidence that I could achieve anything.”

Michael Eboda, CEO of Powerful Media, said: “The Powerlist continues to be a great showcase, acknowledgement and reminder of the amazing individuals of African, African Caribbean and African American heritage we have in the UK and I would like to congratulate each and everyone on the list.”

“Jacky Wright is a true professional who well deserves being recognised as the UK’s most powerful black Briton on the 2022 Powerlist. She is a shining example of professional excellence and this is evident through the roles she has been appointed to throughout her illustrious career. She is a role model to many, and I applaud the great work she is doing at Microsoft US.”

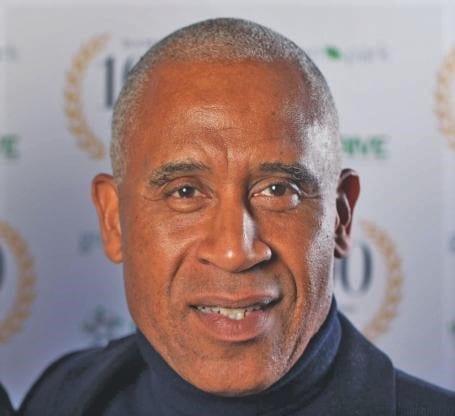

David Adetayo Olusoga OBE was born in 1970 and is a British historian, writer, broadcaster, presenter and film-maker. He is Professor of Public History at the University of

Manchester. He has presented historical documentaries on the BBC and contributed to The One Show, a BBC daily programme, and The Guardian newspaper.

Early life and education: Olusoga was born in Lagos, Nigeria, to a Nigerian father and British mother. At five years old, Olusoga migrated to the UK with his mother and grew up

in Gateshead, Tyne and Wear. He was one of a very few non-white people living on

a council estate. By the time he was 14, the National Front had attacked his house on more than one occasion, requiring police protection for him and his family. They were eventually forced to leave as a result of these racist attacks. He later attended the University of Liverpool to study the history of slavery, and in 1994, graduated with a BA (Hons) degree in History; followed by a postgraduate course in broadcast journalism at Leeds Trinity University.

Career: Olusoga began his TV career behind the camera, first as a researcher on the 1999 BBC series Western Front. Realising that Black people were much less visible in the media and historically, Olusoga became a producer of history programmes after university, working from 2005 on programmes such as Namibia: Genocide and the Second Reich, The Lost Pictures of Eugene Smith and Abraham Lincoln: Saint or Sinner?.

Subsequently he became a television presenter, beginning in 2014 with The World's War: Forgotten Soldiers of Empire, about the Indian, African and Asian troops who fought in the First World War, followed by several other documentaries and appearances on BBC

One television's The One Show.

In 2015 it was announced that he would co-present Civilisations, a sequel to Kenneth Clark's 1969 television documentary series Civilisation, alongside the historians Mary

Beard and Simon Schama. His most recent TV series include Black and British: A Forgotten History, The World's War, A House Through Time and the BAFTA award-winning Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners.

Olusoga has written stand-alone history books as well as ones to accompany his TV series. He is the author of the 2016 book Black and British: A Forgotten History, which was awarded both the Longman–History Today Trustees Award 2017 and the PEN Hessell-Tiltman

Prize 2017.

His other books include The World’s War, which won First World War Book of the Year in 2015, The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism (2011) which he co-authored with Casper Erichsen, and Civilisations (2018). He was also a contributor to the Oxford Companion to Black British History, and has written for The Guardian, The Observer, New Statesman and BBC History magazine. Since June 2018 he has been a member of the board of the Scott Trust, which publishes The Guardian.

Powerlist: Olusoga was included in the 2019 and 2020 editions of the Powerlist, an annual ranking of the 100 most influential Black Britons. In the 2019 New Year’s Honours List. Olusoga was awarded an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (or OBE) for services to history and to community integration.

Professorship: On appointing him as a professor in 2019, the University of Manchester described him as an expert on military history, empire, race and slavery, and "one of the

UK's foremost historians". In May 2019 Olusoga gave his inaugural professorial lecture on "Identity, Britishness and the Windrush" at the University of Manchester.

In response to the global Black Lives Matter movement with protests sparked by the killing of George Floyd, an unarmed African American by the Minnesota Police in the USA,

Olusoga's Black and British: A Forgotten History was re-broadcast on the BBC and made available on BBC Player] along with several other documentaries fronted by him.

Desert Island Discs: In January 2021, Olusoga appeared on BBC Radio 4's, Desert Island Discs, where he discussed his childhood experiences of racism and his love of Blues music. Among his choices of music were "Can't Blame the Youth" by Bob Marley and the

Wailers and "Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground" by Blind Willie Johnson. His luxury item was an acoustic guitar and his choice of book was The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell: An Age Like This, 1920–40.

Professor Dame Donna Kinnair DBE is a British nurse and has been Chief Executive and General Secretary of the Royal College of Nursing (or RCN) since August 2018. She has specialised in child protection, providing leadership in major hospital trusts in London, teaching, and advising on legal and governmental committees.

She initially pursued a maths degree but decided not to complete it. She later returned to education having been encouraged by an occupational health nurse to take up nursing. Kinnair credits her experience growing up with an asthmatic father with showing her the impact nursing could have on people. She attended the Princess Alexandra School of Nursing at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel in 1983 to train as a nurse.

Following her training, Kinnair worked with HIV and intensive care patients in east London. She subsequently worked as a health visitor in Hackney, Newham and Tower Hamlets and pursued further studies, gaining a master's degree in medical law and ethics. Her new qualifications led her to focus on child protection in south London. Notably, she was one of four expert advisers in the 2001 Laming inquiry into the death of eight year old Victoria Climbié.

Kinnair has held several senior positions in the healthcare sector including the following:

o Strategic Commissioner for Children's Services

at Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham health authority;

o Clinical Director of Emergency Medicine at Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals Trust;

o Executive Director of Nursing, southeast London Cluster Board; and

o Director of Commissioning, London Borough of Southwark and Southwark Primary Care

Trust.

Further to her positions in the healthcare sector, Kinnair has taught medical law, ethics and child protection in many countries including Britain, New Zealand, Russia and Kenya.

In 2008, Kinnair was made Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 2008 Birthday Honours.

In addition she has provided advice to the UK government on nursing and midwifery through her work with the prime minister's commission in 2010.

In 2015, Kinnair was appointed Head of Nursing of the Royal College of Nursing (or RCN), after which she was promoted to Director for Nursing, Policy and Practice in 2016.

In August 2018, she was appointed acting Chief Executive and General Secretary before being confirmed on a permanent basis in April 2019.

In 2020, Kinnair was recognised for her influence, having been listed in the 2020 Powerlist, which is an annual listing of the 100 most influential Britons of African and African Caribbean background.

Leroy Logan was born in Islington, London, to Jamaican parents. Logan attended Hackney Community College where he studied A-levels in biology, chemistry and physics. After leaving school, he attended the University of East London, from 1976 to 1980, where he earned a BSc degree in Applied Biology. In 2013, the University of East London awarded him an honourary PhD for his services to policing.

Logan is a British author known for his significant contributions to policing in the UK. He was both a founding member of the Black Police Association and its chairman for 30 years.

Logan left the Metropolitan Police at the rank of superintendent having been involved in the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, the inquiry into the killing of Damilola Taylor and the organisation of the London 2012 Olympics.

In 2020, Logan released his first book ‘Closing Ranks, My Life as a Cop’ which detailed his time as a senior police officer in London. In the winter of the 2020, a programme

called Small Axe (an anthology series created by Sir Steve McQueen, the renowned British director) was aired on British television. Part three of this five part series, which dramatised Logan's time in the Metropolitan police service, aired on BBC One in the UK and Amazon Prime in the United States. Logan was played by the renowned actor John Boyega.

Personal life and career: Logan was awarded a six figure sum in 2003 by the Metropolitan Police following an investigation over a hotel bill. His autobiography Closing Ranks: My Life as a Cop was published in 2020.

Logan joined the police force in 1983, having previously worked as a research scientist. He was inspired to join the police after witnessing two officers assaulting his father.

He was described by The Voice newspaper as "one of the Black officers who helped change the Met." In 2000, Logan was awarded an MBE for his work in advancing policing.

As chairman of the Black Police Association he was involved in the Stephen Lawrence enquiry and the enquiry into the killing of Damilola Taylor. In 2013, Logan retired from the Metropolitan police service; and he remains an executive member of the National Black Police Association and a founder member of the Black Police Association Charitable Trust.

Homerton College University of Cambridge announced the election of Lord Woolley of Woodford as its next Principal. Lord Woolley will succeed Professor Geoffrey Ward on 1 October 2021.

Simon A. Woolley, Baron Woolley of Woodford, Knight Bachelor (or Kt) is a political and equalities activist. He has a first degree in Spanish and Politics from Middlesex University; and a Master of Arts, post graduate degree, in Hispanic Literature from Queen Mary University of London. He is the founder and director of Operation Black Vote (or OBV) and the Advisory Chair of the UK’s Race Disparity Unit.

Woolley become engaged in British politics by joining the campaign group Charter 88. He started to research the potential impact of the Black community vote, which Woolley argued could influence electoral outcomes in marginal seats. These findings encouraged him to launch OBV in 1996.

The OBV launched voter registration campaigns, an App to inspire and inform Black and minority ethnic (or BME) individuals; and it worked with Saatchi & Saatchi on a pro bono advertising campaign. Woolley also worked to empower communities and to introduce better politics education into the school curriculum.

The Esmee Fairbairn Foundation estimated that Woolley's OBV efforts encouraged millions of people to vote. Much of his work has been around nurturing BME civic and political talent. The then Home Secretary Theresa May, said in a 2016 Westminster speech: "Today we celebrate a record number of BME MPs in Parliament, 41. British politics and British society greatly benefits when we can utilise diversity’s teaming talent pool. That’s why today we are announcing that in the months ahead we will begin a new MP and business shadowing scheme."

In 2008, the Government Equalities Office released Woolley's report, “How to achieve better BME political representation.” Woolley was appointed in 2009 to the Commissioner for Equality and Human Rights Commission (or EHRC).

He launched two governmental investigations, including REACH, which looked to tackle the alienation of black youth, as well as working with Harriet Harman MP on the political representation of BME women. He worked with Bernie Grant MP, Al Sharpton (US community leader) and Naomi Campbell (a super model) and Jesse Jackson (a US community leader) on grassroots campaigns highlighting racial discrimination.

In 2017 OBV, the Guardian newspaper and Green Park Ltd launched the “Colour of Power,” to date the most in-depth look at the racial make-up of Britain's top jobs across 28 sectors that dominate British society. The results were reported in The Guardian: "Barely 3% of Britain’s most powerful and influential people are from BME groups, according to a broad new analysis that highlights startling inequality despite decades of legislation to address discrimination."

He has called for local councillors to become more diverse, after it emerged that of the 200 councillors in South Gloucestershire, Bath and North East Somerset, and North Somerset, not one was from a BME background.

In May 2019, Woolley and OBV launched a ground-breaking report into more than 130 key local authorities that emphasised the lack of BME representation. In over one third of them, many with sizeable BME populations, they either had no or just one BME councillor.

Along with former Downing Street advisors - Nick Timothy and Will Tanner - Woolley is seen as the inspiration and one of the architects for the Government’s Race Disparity Unit, and became its Advisory Chair.

He has worked with the Open Source Foundation on their global drugs policy projects. He secured £90 million of funding to encourage disadvantaged young people into work. When OBV started, there were just 4 BME MPs; but as of 2019, there are more than 50.

Woolley has received a number of awards and honours as shown below:

He was included in the annual Black Powerlist every year since 2012.

He was selected as one of the Evening Standard's Most Influential People in2010.

In 2010 and 2011 he was selected as one of the Daily Telegraph's 100 Most Influential People.

In 2012 he was awarded an honorary doctorate for his equality efforts from the University of Westminster.

He received a Knighthood (Kt) in the June 2019 Queen’s Birthday Honours for his services to race equality.

He was nominated for a life peerage, sitting as a Crossbencher in the House of Lords, by the Prime Minister Theresa May in her 2019 Resignation Honours List. On 14 October 2019 he was created Baron Woolley of Woodford in the London Borough of Redbridge.